Every dog owner — but especially those who have large, deep-chested dogs — should know the signs and symptoms of two life-threatening conditions: gastric dilatation (GD) and gastric dilatation-volvulus (GDV). Read on to learn more about why these conditions are medical emergencies, as well as the risk factors, signs and symptoms, and treatment.

What are bloat, gastric dilatation and GDV?

“Bloat” is the everyday name for two canine stomach disorders. The first is gastric dilatation, a condition in which the stomach fills with gas, with or without fluid, and expands in size. The second is gastric dilatation-volvulus, a condition in which the stomach becomes gas-filled, distended and twisted on itself, resulting in an obstruction. Although bloat and GDV are used interchangeably, they aren’t truly synonymous.

Which comes first? Stomach bloating or stomach twisting?

According to information presented during the 2003 Tufts’ Canine and Feline Breeding and Genetics Conference, 25 percent of bloat cases start with gastric dilatation. As the stomach dilates and expands, the pressure in the stomach rises. The increased pressure compresses both the entrance and exit of the stomach, trapping gas and stomach contents. The other 75 percent of cases result from the stomach twisting first, blocking movement of gas, food and fluids in and out of the stomach.

Regardless of whether a dog’s stomach bloats and twists, twists and bloats, or simply bloats, the consequences of trapped stomach contents are serious.

An enlarged stomach that’s many times its normal size interferes with blood circulation, not just in the stomach wall but also in the ability of blood to return to the heart from the abdomen. And a twisted stomach cuts off the blood supply to the stomach. When tissues are deprived of blood and oxygen long enough, the cells of those tissues start dying.

The increased pressure and size of the stomach can result in rupture of the stomach wall. In addition, an enlarged stomach puts pressure on the diaphragm, interfering with the lungs’ ability to adequately inflate and hampering normal breathing.

What causes GDV?

Veterinarians still don’t know what causes GD and GDV, although they have identified risk factors.

Statistically, veterinarians know that large, deep-chested breeds are more likely to experience GDV. A study conducted in the mid-1990s using data from 12 university veterinary hospitals found five breeds have the highest risk of GDV: great Dane, Weimaraner, Saint Bernard, Gordon setter and Irish setter. Other breeds with increased risk of GDV include standard poodles, German shepherds, Doberman pinschers, basset hounds and boxers.

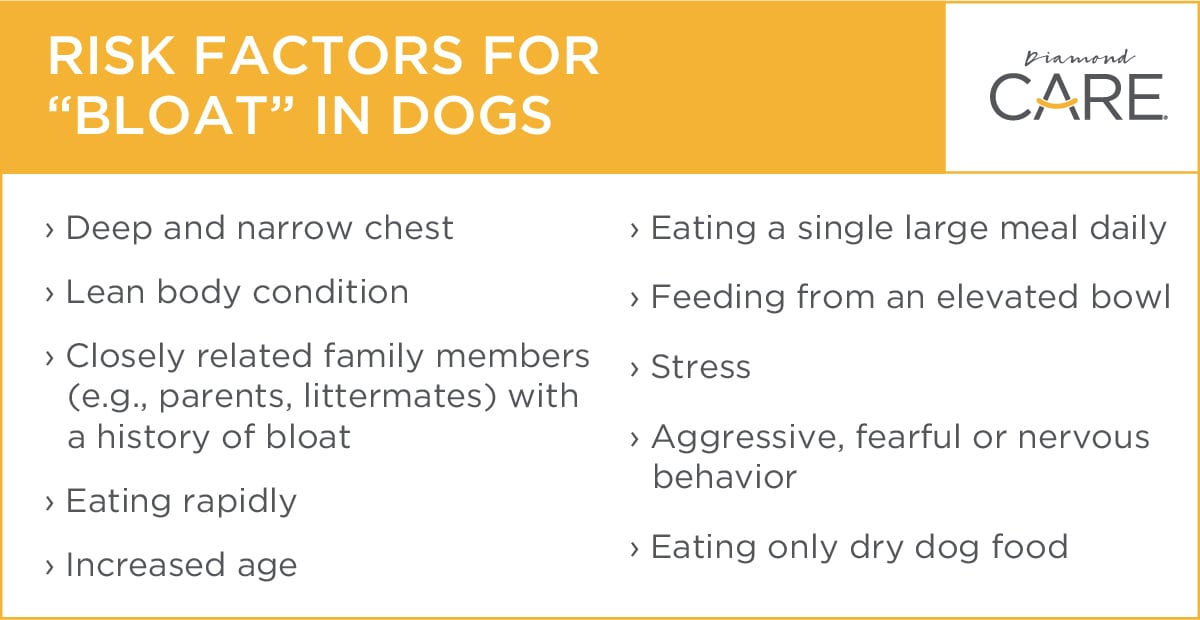

Several other factors increase a dog’s risk for developing bloat and GDV (see graphic).

While the condition is more common in large and giant breed dogs, it’s important for dog owners to know that any dog can develop bloat.

Know the signs and symptoms

Dogs who are experiencing bloat or GDV can exhibit several signs and symptoms. Keep in mind that not all dogs will show all of the signs listed. Plus, even some of the most common signs and symptoms aren’t always easy to recognize.

- Pacing and restlessness. Dogs with bloat or GDV have trouble getting comfortable and lying down. Pacing and restlessness are among the most obvious and early signs, so take note!

- Hard, distended or bloated abdomen. If your dog is very large, deep chested or especially furry, an enlarged stomach may not be obvious because the stomach may be hidden by the rib cage.

- Unproductive vomiting/repeated dry retching. A dog with GDV may try to vomit without bringing anything up. However, you may see a large amount of thick, stringy saliva.

- Excessive drooling. Dogs with this condition experience nausea, and excessive saliva, along with “lip smacking,” can be signs of nausea.

- Fast, labored or difficulty breathing. An enlarged stomach puts pressure on the diaphragm and decreases the amount of chest space available for the lungs to work. Pain, distress and changes in the body’s acid-base balance also contribute to breathing difficulties.

On physical examination, your veterinarian may find rapid heart and pulse rates, pale mucous membranes and a prolonged capillary refill time, an indication that blood isn’t flowing adequately and that the dog is going into or in shock. A dangerous, abnormal heart rhythm called premature ventricular contractions, or PVCs, is associated with GDV and must be ruled out.

Is it bloat or GDV?

Gastric dilatation and GDV are diagnosed based on a dog’s history, breed, age and physical exam findings. To help determine if the condition is bloat or GDV, X-rays will be needed. However, the veterinarian will want to make sure a dog is stable first.

How GDV and bloat are treated

Several steps must be taken to save a bloated dog’s life. And none of them are steps that you — or any dog owner — should do at home. The only correct way to treat GDV and bloat are to seek immediate veterinary care.

The first goals of treatment are to stabilize the dog and release the pressure in the stomach as soon as possible. The veterinarian may first try to pass a tube through the mouth into the stomach. Once the tube enters the stomach, gas can readily escape. Any excess fluid and/or food can then be removed via gravity and suction. If a tube can’t be passed into the stomach because of twisting, pressure can be released by inserting a large-bore needle and catheter directly into the stomach through the skin.

Treating shock and assessing the heart rhythm also must start immediately to help stabilize a dog with GDV or bloat. Intravenous (IV) fluids and appropriate medications play critical roles in reversing shock and managing pain. And since an abnormal heart rhythm may not appear until later, continual EKG monitoring may be needed.

Once the dog is stable and able to undergo anesthesia, surgery is performed to assess the stomach, spleen and other nearby organs, remove any dead or dying tissues, and return the stomach to its normal position. The stomach will be tacked to the abdominal wall, a procedure called gastropexy, to help decrease the likelihood that the stomach will rotate again. Without gastropexy, the rate of GDV recurrence can be as high as 75 percent.

If you are concerned that your dog could be at risk for GD or GDV, talk with your veterinarian. Knowing what signs and symptoms to watch for can provide peace of mind. And be sure to know where to take your dog during overnight or Sunday hours for emergency care.

RELATED POST: Is It a Sensitive Stomach or Something More Serious?